Philipse Manor Hall State Historic Site has a number of fireplaces, some of them more intact than others. But while many visitors are dazzled by our beautiful delft tile fireplace surrounds, or the intricate woodwork, few notice the cast iron objects hiding in the shadows: firebacks.

Sometimes called "chimneybacks," firebacks were cast iron plates designed to protect the brick backing of fireplaces from overheating or "burning out," which would lead to spalling or crumbling bricks, jeopardizing the structural integrity of the fireplace. They had an added bonus of absorbing and radiating heat after fires were banked for the night.

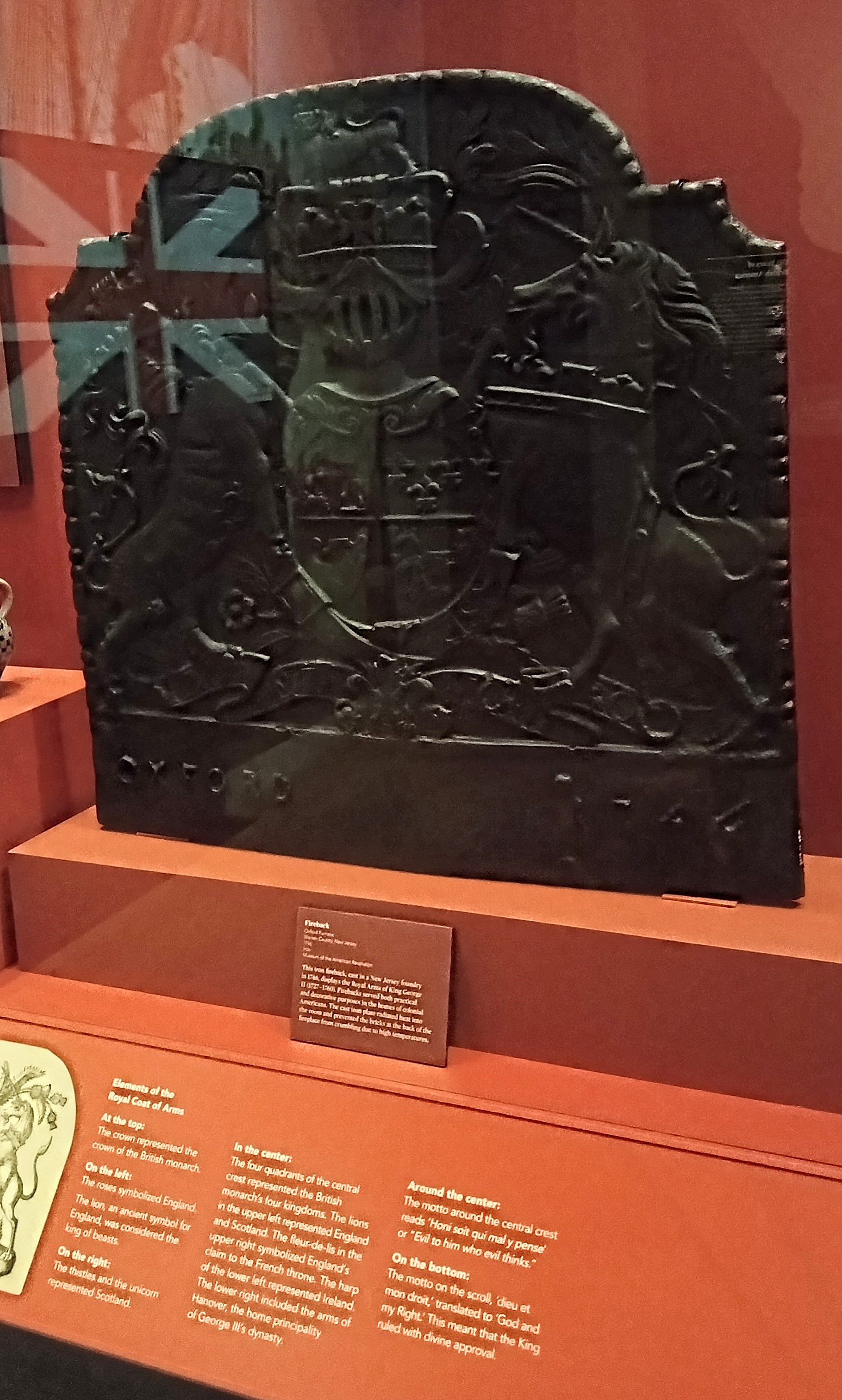

Earlier this spring, I was touring Philadelphia’s Museum of the American Revolution and spied this 18th century fireback. It’s nearly identical to ones we have at Philipse Manor Hall.

Because fireplaces were often focal points in the home, firebacks were often designed to be decorative as well as functional. According to the Museum of the American Revolution's website, “Symbols of the British empire decorated household goods of all kinds. This iron fireback, cast in a New Jersey foundry in 1746, displayed the Royal Arms of King George II (1727-1760). Firebacks served both practical and decorative purposes in the homes of colonial Americans. The cast iron plate radiated heat into the room and prevented the bricks at the back of the fireplace from crumbling due to high temperatures.”

At Philipse Manor Hall, our fireplaces were bricked up twice prior to the 1911 American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society restoration. Once reopened, iron panels bearing the Royal coat of arms of Great Britain were discovered, likely dating to between 1714 and the Revolutionary War period. The coats of arms feature a ribbon with of the Royal motto in French: “honi soit qui mal y pense.” (“Shame on anyone who thinks evil of it”). Philipse Manor Hall has two of these firebacks, one in the "Great Britain" fireplace, and the other in the Rococo fireplace.

I discussed the firebacks with the historians at New York’s Historic Preservation department, and they pointed me to another British coat of arms fireback at Clermont, the family seat of the Livingston family—relatives of the Philipses by marriage—who owned huge swaths of the Hudson riverfront, upstream. The original Clermont mansion was built around 1740 by the second Robert Livingston. During the Revolutionary War, in 1777, the British punished the Livingstons for being sympathetic to Rebel causes by torching their home and twenty other buildings. The mistress of the house, Margaret Beekman Livingston, petitioned the Governor of New York to secure militia exemptions to acquire men for a rebuild. After generations of use by the Livingston family, the second mansion and its surrounding 500 acres were acquired by the State in 1962.

Geoff Benton, Clermont’s site manager told us “I found two conflicting pieces of information about [our fireback’s] history. One was that it was in the house when the state took over. The other stated that it was found during an archeological dig done in the area where the Livingstons dumped most of the fire debris in 1778. So, if that is true, it is likely that Robert ‘The Builder’ Livingston or his son Judge Robert R. Livingston was the original owner."

He continued, "Many of our fireplaces are backed with metal, which is a 19th century change, I believe.” Clermont has two firebacks of note. “The one House of Hanover coat of arms has been dated to 1740-1750. It was made by Oxford Furnace in Warren County, New Jersey. That piece is in our drawing room.”

Manufacturer Oxford Furnace operated in Oxford, NJ, about an hour and forty minutes due west of Philipse Manor Hall. Mines on Oxford Mountain provided iron ore throughout the 18th and 19th centuries for the industry. Oxford Furnace firebacks are also in the collections of Colonial Williamsburg, the Pieter Bronck House, the Mercer Museum, Morristown National Historic Site, Historic Deerfield, The Metropolitan Museum Museum of Art, and Winterthur, amongst others. We’re not sure about the origin of our firebacks, as they do not have a maker’s name molded in, but the Oxford Furnace seems a likely source.

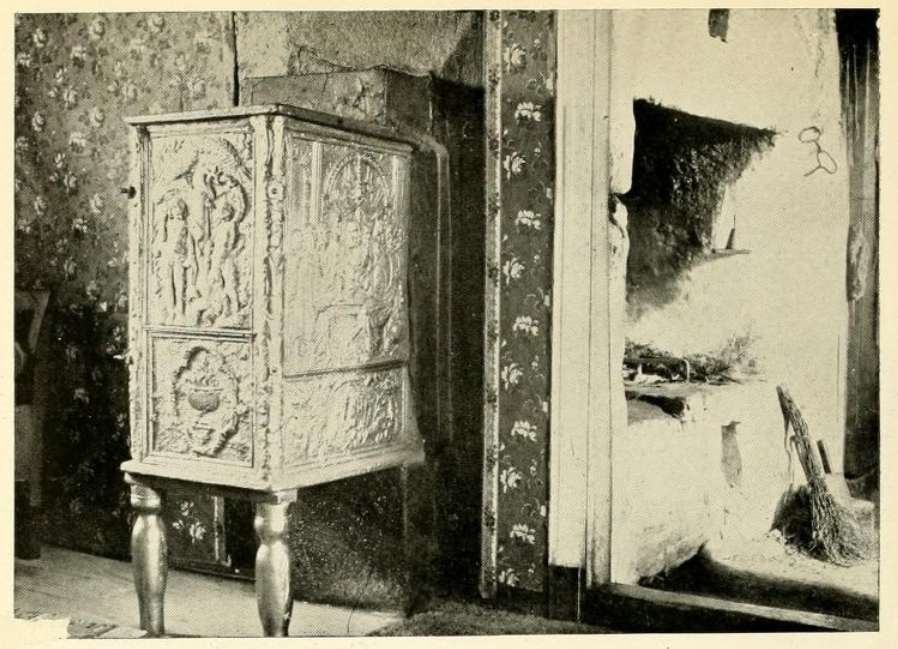

In our Biblical tile and Connected Manors fireplaces, both firebacks are old stove plates, cast in relief with a representation of Elijah being fed by ravens (I Kings:17). The markings on one, “17BSDW60,” indicate that it was cast in 1760 by master ironworkers Benedict Schroeder and Dietrich Welker, owners of the Shearwell Furnace in Pennsylvania. The plate was part of a “five-plate non-ventilating (or jamb) stove.” This style of stove was introduced in the mid-to-late eighteenth century by German immigrants.

Examples of this type, many with Biblical stories cast on them, can be found throughout the region. They heated rooms more effectively than open fireplaces. The shifting technology of room heating would advance quickly following the Revolutionary War as more iron works were created. The plate was used as a traditional fireback, and no historic documents reference when it was installed or by whom, but it seems likely that as old stoves were damaged or needed replacement, that repurposing the plates as firebacks was common.

The next time you visit Philipse Manor Hall, we encourage you to view these firebacks in person. Although today fires are considered too dangerous to have in historic houses, firebacks are a good reminder of the original purpose and function of these historic fireplaces. If you'd like to learn more about our fireplaces, or other architectural details about Philipse Manor Hall, please explore the Architecture section of our website.

The Bible In Iron: Or, Pictured Stoves and Stove Plates of the Pennsylvania Germans by Henry C. Mercer (1914).

"History of Oxford Furnace," Warren County (NJ) Bicentennial Cultural & Heritage Advisory Board.

David C. Lucas is an interpreter at Philipse Manor Hall, giving public tours, working the front desk, and contributing to the website and social media. In his previous career, he spent years at Macy’s in Manhattan as a Graphic Designer and Art Director. Subsequently, he taught Design for several semesters at New York City University of Technology and worked at Rye Playland. He occasionally serves as a docent at the Hudson River Museum, and is the Trail Maintainer for the German Hollow Trail of the Catskill Forest.