First-hand accounts of the American Revolution are rare. Even rarer are first-hand accounts of enslaved people from this time period. But a recently digitized collection of interviews reveals an enslaved man’s perspective of the Revolutionary War in Westchester.

Prince Gedney was born into slavery in Scarsdale, Westchester County, in 1758 and sold to the Gedney family while still an infant. If he knew his parents at all, he saw them rarely. When the Revolutionary War erupted in 1776, he was 18 years old. His enslaver at this time was Absalom Gedney, a Loyalist who had established a farm on Chatterton Hill on the eastern edge of the Philipsburg Manor, where modern-day Greenburgh meets White Plains. Prince and the Gedneys experienced war directly when the Battle of White Plains came to Chatterton Hill in the fall of 1776. Prince remained on this farm with Absalom throughout the war, often acting as his agent in British-held Manhattan, where he sold farm goods on behalf of the family.

We are extremely fortunate to have two interviews with Prince Gedney, conducted in 1848 and 1850 by John MacDonald at the end of Gedney’s life.1 They are part of the McDonald Interviews, also known as the McDonald Papers, a compendium of first hand accounts of the Revolutionary War recorded by MacDonald throughout the county and what is now the Bronx. Recently digitized by the Westchester County Historical Society, the interviews are virtually unique because they record the perspectives of average people who were neither wealthy nor highly-ranked in the military.2

Even more unusual than testimonies from working- and middle-class people are those enslaved men and women, who are all but invisible in the surviving record. Gedney is one of only two Black men that were interviewed by MacDonald, the other being John “Jack” Peterson, a free man during the war who fought bravely on the American side on multiple occasions.

%2C%20John%20Singleton%20Copley%2C%201777-78%20-%20Detroit%20Museum%20of%20Art.jpg)

Prince was extremely forthright and affable about his experience and rarely references directly the fact that he was enslaved. Although the Gedney family were Loyalists, Prince did not seem to have had any particular affiliation, instead speaking in a frank – and often unflattering – manner about combatants on both sides.3 In this he is similar to a great many other individuals that were interviewed by MacDonald, many of whom were concerned less with independence and more with simply surviving and keeping themselves fed during the conflict.[4]

The Gedneys regularly sent Prince into Manhattan to buy and sell goods for the family farms.5 Enslaved individuals were useful for such purposes during the war because their race and status made them “invisible” to a degree and non-threatening to military personnel (one of the main reasons that they also made excellent spies)6 In the case of the Philipses, we see this demonstrated in Frederick Philipse III’s use of Diamond, who he enslaved, as a carrier of letters to his wife Elizabeth during his imprisonment in New Rochelle in 1776.7

As Kenneth Daigler wrote in his 2014 analysis of espionage during the Revolution: “African American agents were especially valuable because their activities were considered unalarming based upon their social status. Slaves and freemen were present in large numbers and readily accepted — or, rather, ignored — as part of the town’s daily commerce and street scene.”8 The ubiquity of enslaved people moving about the streets of Manhattan during the war – when the city’s Black population hovered around 15% – conducting business on behalf of their enslavers is well attested.9

One of the most revealing anecdotes in the interviews concerns a day when Prince lost one of the passes that the British authorities issued to outsider civilians wishing to pass in and out of Manhattan. As a result, he was forced to go to Mount Morris (the Morris-Jumel Mansion, built by Roger and Mary Philipse Morris, is still standing at West 160th Street and Edgecombe Avenue) to request a replacement from the Hessian commander headquartered there:

“...Sometimes, I went into New York to buy. On such occasion I got a pass from General Horriman or some other Hessian officer, whose quarters generally were at Morris’s house. The pass allowed me to go in the city and purchase the articles which were specified. Once I lost my pass and went back for another. This provoked General Horriman who said ‘What for you lose your pass? Be careful. Suppose you lost this, I give you no more.’ After scolding awhile he gave me a new permit and then asked, ‘Vat will you trink?– Here’s prandy, rum and gin.’ I answered that I would take a glass of spirits which he gave me accordingly.”10

The relaxed, humorous manner in which Prince relates the tale – even mimicking the German accent of the commander – is a great example of the ways in which the Interviews can personalize the war for modern readers. Also noteworthy is that the Hessian, after berating Prince for some time as if he were a child, suddenly softens and offers him a drink. It is a curious mixture of condescension and courtesy, and one wonders what motivated the apparently friendly gesture.

Some of Prince’s stories are about military and other “Historical” events (e.g., British troop movements ahead of the Battle of White Plains, the tearing down of a Liberty Pole erected by local Patriots, the sabotage of Patriot cannons by Loyalists). For the most part, however, his focus is on the deadly skirmishes that so often accompanied the theft of cattle and horses by raiders from both armies. A lawless “Neutral Zone” during the war, Westchester’s farmers were terrorized by these marauding bands. Those on the British side were usually known as “Refugees” while those on the American side tended to be called “Skinners”.11 At least half of the violence in the county – even when it had an ostensibly military purpose – was fundamentally about capturing and gaining access to horses, cattle, crops, and other resources, and Prince’s commentary reflects this well.

A rather loquacious individual (his interviews are among the longest in the collection), his descriptions of “victual warfare”12 are extraordinary for their vividness and unsparing nature. One episode that he appears to have witnessed first-hand was a street battle in White Plains between Refugees and Skinners. The Skinners had just snatched several head of cattle from Loyalist drovers in the South Bronx and brought them back to White Plains. The leader of this Skinner group, a Captain Honum, was an old hand at pilfering Loyalist livestock, having just acquired the horse of one of the main Refugee leaders, Samuel Kipp.

Unfortunately for the Skinners, the place in the Bronx where they waylaid the Tory cattlemen was very close to the primary Refugee encampment at Morrisania, under the command of James DeLancey. The drovers immediately called on the Refugees to recapture the cattle and punish their attackers. Off went a large Refugee band under Kipp to pursue Honum’s group, which they eventually tracked to White Plains. Seeing the stolen cattle – as well as his own horse being ridden by Honum – Kipp called out passionately for their destruction:

“‘Pursue, boys! pursue! Down with them and no quarter!’ The Skinners who were now all mounted spurred their horses onward to their utmost speed, but the strong efforts which in moments of extremity men so often make and make successfully were unavailing upon this occasion. All but the leader were overtaken and cut to pieces without mercy… One of the first skinners overtaken was a young man who, after receiving a great many sword cuts, was left upon the ground for dead. He was, however, still alive, and while the Refugees were in pursuit of Honham’s party, crawled a short space and concealed himself behind the roots of a tree which had blown down; but, on their return, Kipp’s men discovered the wounded skinner and literally cut him limb from limb. One young man they attempted to take below a prisoner, but when placed on horseback he fainted from loss of blood, having received many wounds. Supposing him dead, they left him behind telling Mr. Hart of Purdy’s Lane to bury him; but the gentleman finding the prisoner still alive had him carefully nursed, called in surgical aid and was at length gratified by his recovery. This young man and Honum were the only two who escaped. All the rest were killed outright.”13

The episode that Gedney recounts is one of a great many similarly vicious and deadly instances of victual warfare described in the Interviews (i.e., having to do with control of livestock and other resources) in the Neutral Zone. Isolated on Manhattan, the British were much less capable of producing their own food than parties in the Neutral Zone and further north, and had to rely heavily on foodstuffs imported from colonies in the Caribbean or even Europe. Hence the theft of Manhattan-bound cattle by American raiders like Honum’s band would have inflicted real pain on the enemy in addition to giving sustenance to Washington’s forces.

Like so many other Loyalist combatants, members of the Gedney family who had served in the British military fled to Canada after the war.14 Curiously, however, Prince’s enslaver Absalom – despite serving as a captain in the King’s army – does not appear to have left Westchester. Why this was so is anyone’s guess. Despite his rank and Loyalist orientation, he may not have actually fought, which could have saved him, or perhaps he was able to negotiate his way out of banishment by sacrificing some of the family’s lands to the new government.

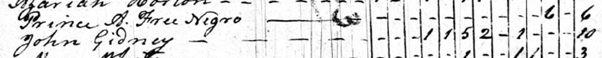

Absalom Gedney died shortly after 1790, and appears to have manumitted Prince upon his death, because in the 1800 census for Westchester he is listed as “Prince A. Free Negro” (one of only a handful of such entries in this decade’s census). Absalom was under no legal obligation to manumit in the 1790s – abolition would not take full effect until 1827 - so it may indicate a fairly progressive mindset on his part, or it may simply mean that Prince, who was nearly 40 by this time, had outlived his perceived usefulness.15

Prince’s name is listed in the 1800 census adjacent to that of John Gidney (an alternate spelling of Gedney), another member of the family who had perhaps inherited Absalom’s property. This suggests that Prince and his family of six lived directly beside his former enslavers after his manumission (census takers typically moved from door to door in the era, with the result that the names tend to appear in a roughly geographical order). This remained the case for the next thirty years.16 Even after John’s death, Prince continued to live beside White members of the Gedney family until his own demise in 1855.17

Absalom’s early manumission of Prince, together with the fact that Prince continued to live beside the Gedneys for the rest of his life, may indicate an unusually amicable relationship between them, or simply a desire on Absalom’s part to provide for Prince in his old age. This was not uncommon in the era, especially when an enslaver felt an individual had been particularly loyal and hard working.18

Prince Gedney died in 1855 at the extremely advanced age of 99 years old. He was a living repository in his own time and continues to be one today as a result of the McDonald interviews. That his descendants continued to live in White Plains long after he were gone is suggested by the many African American individuals with the surname of Gedney that appear in census records for the remainder of the nineteenth century. If you would care to read the interviews in full they can be accessed at:

https://collections.westchestergov.com/digital/collection/mcdonald/id/1454/rec/1

https://collections.westchestergov.com/digital/collection/mcdonald/id/1966/rec/2

Author Bio

J. Keith Doherty is a Westchester County native who grew up along the Old Croton Aqueduct. He was a Professor of Art History for twelve years at Boston University and has in recent years been researching the infrastructure, people, and history of Westchester. He is currently a museum interpreter for Philipse Manor Hall State Historic Site.

[1] “Interview with Gedney, Prince.” Dec. 9, 1848, 898-902, Westchester County Historical Society; “Interview with Gedney, Prince.” Oct. 22-23, 1850, 1046-56, Westchester County Historical Society.

[2] The full McDonald Collection, digitized by Westchester County Historical Society.

[3] Eleanor Phillips Brackbill. “Isaac Gedney Jr. and the Neutral Ground.” Westchester Historian 81.2 (2005): 36-57.

[4] See Todd Braisted. Grand Forage 1778. Yardly, Pennsylvania: Westholme (2016), x.

[5] “Interview with Gedney, Prince.” Oct. 22-23, 1850, 1048-1050

[6] Kenneth Daigler. Spies, Patriots, and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War. Georgetown University Press (2014), 232-40.

[7] Sarah Wassberg Johnson. “The Imprisonment of Frederick Philipse III.” Philipse Manor Hall Blog (2014).

[8] Daigler 2014, 237.

[9] Judith Van Buskirk. “Crossing the Lines: African-Americans in the New York City Region during the British Occupation,1776-1783.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 65 (1998): 74-100.

[10] “Interview with Gedney, Prince.” Oct. 22-23, 1850, 1048-1050; unfortunately “Horriman” cannot be verified as a Hessian General, but General Knyphausen was headquartered at Mount Morris for most of the war.

[11] The Refugees were also known, somewhat more derogatorily, as “Cowboys” (a name that referred to their regular theft of cattle). Gedney’s use of the term “Refugee”, which refers to the displacement of many of the men from their homes by Patriot forces, suggests relative sympathy and may reflect his Loyalist milieu.

[12] This phrase is used by Rachel B. Herrmann in her No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution (Ithaca: Cornell University Press (2019)).

[13] “Interview with Gedney, Prince.” Oct. 22-23, 1850, 1050-1051.

[14] Grenville Mackenzie. “Gedney” in Families of the Colonial Town of Philipseburgh, I. Unpublished. Westchester County Historical Society.

[15] 1800 U.S. Census, Westchester County, New York, population schedule, White Plains.

[16] US Census records, 1810-1850, Westchester County, New York.

[17] ibid, 1810-1850.

[18] Special accommodations or provisions for individuals that had been enslaved for long periods are often seen in wills from this time. See e.g., John Jay’s treatment of Plato, Zilpah and others who had served his family for long periods (David Gellman Liberty’s Chain: Slavery, Abolition, and the Jay Family of New York. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press (2022), 75-76, 110-11).